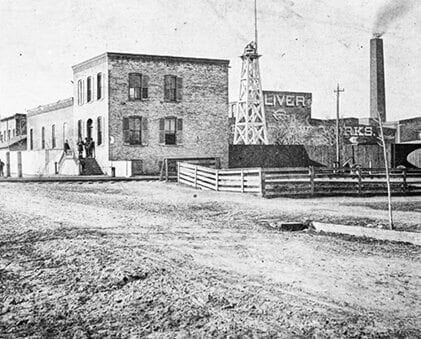

THE OLIVER CHILLED PLOW WORKS

Plow sales in 1878 reached 62,779. A total of 30 to 40 railroad cars loaded with 5,000 to 7,000 plows left the new “Upper Works” at a time, for shipment from coast to coast. In November 1878, Brownfield, who had been president for almost nine years after the resignation of George Milburn, tendered his resignation, and in January 1879, James Oliver was elected president. Prior to that, James had held the title of superintendent.

Meanwhile, “branch houses” were being established across the land to handle distribution of the plows. The size of the Oliver company simply overwhelmed its opponents, including the South Bend Chilled Plow Company, which had been organized by Bissell and allegedly used Oliver patents in an attempt to capitalize on the reputation of the Oliver firm, still known as the South Bend Iron Works. The year 1880 was one of great expansion. A record was set in production and sales of plows, new buildings were erected, riding plows were being produced on a large scale, the manufacture of malleable castings was started, and more rail tracks were laid to the Oliver property.

On May 4, 1881, James purchased the Chess and Vincent properties in the

James and his family moved into the new home at 325 W. Washington Street on December 10, 1882, and on January 17, 1883, held a reception for 500 guests who danced in the third floor ballroom and dined on food prepared by a Chicago chef.

James had come a long way from the simple life of a shepherd in Scotland, but in spite of affluence, he remained a simple man with simple tastes, who preferred the heat of his foundry and the dirt of a farm to the elegant surroundings of his new home. This was to be his last residence. James’ wife died in the home in 1902, and he died there on March 2, 1908. The house stood vacant until 1911, when South Bend School City (now South Bend Community School Corporation) purchased and razed it. South Bend Central High School was erected on the site.

At the time of his father’s death, J.D. Oliver was 58 years of age and had begun working in the foundry full time at the age of 16. He had been a director of the factory since he was 20 years old, so the transition from father to son was easily accomplished. Joseph was a financial genius and it is doubtful James would have done so well without J.D.’s financial guidance. While James was frugal, J.D. realized money often was earned by spending some of it. Because of J.D.’s modesty, it was not generally known that James almost always left details of financial management to his son.

At a meeting after the death of his father, J.D. was elected President, Treasurer and General Manager; James Oliver II (J.D.’s son) was named Vice President and Joseph Ford (J.D.’s brother-in-law) was named Secretary. These three were also the directors of the company started by James Oliver. Thus J.D. held almost the entire issue of Oliver company stock; had been named executor of his father’s will; and he was responsible for the plant and more than 2,000 employees.

Annual production at the time was very high. In 1909, J.D. launched plant expansion to double the size of the plant’s footprint and developed plans to expand sales into Russia and build a factory in Canada. The Oliver Opera House block was remodeled and the Oliver Hotel annex, now seven stories tall, was opened a few months later.

In 1911, plant operations started in the new plant the Olivers had built in Hamilton, Ontario. J.D. correctly perceived vast amounts of Canada’s Northwest wilderness would be opened to agriculture, and the plant was part of a plan to get part of that business. On May 1, the first carload of plows was shipped from Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, and by summer’s end, 30,000 plows had been shipped. Among buildings constructed in Hamilton that year were two large docks to provide for two lake carriers to be used for shipping Oliver products. J.D. had contracted with International Harvester Company to handle distribution and sales for the Oliver Canadian plant. This satisfactory arrangement for both companies continued until 1919 when the Olivers sold the Hamilton plant to International Harvester.

Farming in the United States was steadily becoming mechanized, and the Olivers greeted it fully. A new era had been opened in 1905 when a gasoline engine was mounted on a traction truck to pull several plows. Gasoline farm tractors and gang plows (a large plank that has several plow blades fastened to it) developed rapidly, and on September 30, 1911 a world’s record was set when an Oliver 50-bottom (50 blades) gang plow, pulled by three LaPorte, Indiana-built Rumley Oil-Pull tractors, turned 50, 14-inch furrows at one time, a width of almost 60 feet! That same year three International Harvester tractors pulling a 55-bottom Oliver gang plow set another record by plowing an acre in less than four minutes, a far cry from the days when a farmer walked eight and one-fourth miles behind a team of horses and plow to turn an acre.

When World War I broke out in 1914, J.D. prepared for troubled times. “We shall not attempt to profit by present conditions,” he wrote. After the U.S. entered the war in 1917, J.D. was called to Washington to confer with the nation’s food administrator, Herbert Hoover. But the war not only had to be supplied with arms and food, it also had to be financed. J.E. and Frank Hering, an Oliver Vice-Director, crisscrossed Indiana setting up fund-raising and bond-selling committees in every community. J.D. organized 22,000 schoolteachers to sell thrift stamps for bond purchases through school children to their parents. He often brought down the house when he spoke of “the fires of hell licking their lips in joyful anticipation of the advent of Kaiser Wilhelm” (the German war leader). In addition, to ease the food shortage for employees in South Bend, J.D. established a community garden. Fifty acres near the plant were divided into 50 by 100 foot patches. The families of 301 workers participated in the project. J.D. awarded $50 in gold for the best crop return.

After World War I, demand for tractor-pulled farm implements increased rapidly. It was estimated that 250,000 tractors would be built in 1919. Oliver Chilled Plow Works expected to put 750,000 plows behind the 100,000 tractors International Harvester and Henry Ford and Son would build. To this end the Olivers launched an extensive expansion program, and in the next four years conducted the biggest building and real estate activity, exclusive of the Hamilton plant construction, in the company’s history. More than $3 million went to acquire branch house properties, $160,000 for new buildings at the South Bend plant, and $1 million to erect 160 greatly needed workmen houses.

An innovation at the time was the company’s voluntary introduction of a pension plan, providing for a pension and automatic retirement for an employee who had reached the age of 70 and had been with the company 20 years. No pension was to be more than $100 per month or less than $12.

In a realignment of company responsibility to ease some of his burdens after World War I, J.D. had relinquished some of his duties, including that of plant manager. An operating committee for general management was set to be directly responsible to J.D., who retained the presidency. This committee included James Oliver II, Vice-President; Joseph D. Oliver Jr., Treasurer; H. Gail Davis, Assistant Treasurer; and C. Frederick Cunningham, Secretary, a post that had been left vacant by the death of J.D.’s brother-in-law George Ford in 1917. Gertrude Oliver Cunningham and Susan Catherine Oliver, daughters of J.D., were elected to the board of directors.

When the 1920s arrived, business indicators looked good, but disaster was ahead. Farm prices began to drop. Farmers were unable to pay debts and stopped buying agricultural implements. The company held the largest stock of manufactured goods and the largest stock of raw materials in its history, all purchased at high wartime prices. Because of its strong financial condition, the Oliver Chilled Plow Works weathered the crisis. J.D., however, did not fare so well in spite of the appointment of the operating committee. In October 1923, he fell victim to a four-month illness, described as “tired break-down,” from which he never fully recovered. He resigned many of the outside directorships he held and gave up the presidency of the Purdue University Board of Trustees, on which he had served for 18 years. He returned to his Oliver Chilled Plow Works office February 11, 1924, where he remained active until the business was sold.

In 1923, increased competition from other full-line farm implement companies forced the Oliver Chilled Plow Works to choose between an enormous expansion with a program to include more implements, such as, tractors or joining together with manufacturers of different types of farm tools and establishing its own full-line company.

J.D. Oliver elected to join other manufacturers. At a special meeting of stockholders on February 1, 1929, he was authorized to organize a new company, to be known as the Oliver Farm Equipment Company, and take over the Oliver Chilled Plow Works and the Hart-Parr Company of Charles City, Iowa, a company which manufactured tractors. J.D. also purchased the Nichols and Shepard Company of Battle Creek, Michigan, which made threshing machines, corn pickers and combines. Soon after this merger, American Seeding Machine Company of Springfield, Ohio and the McKenzie Potato Machinery Company of LaCrosse, Wisconsin, were acquired. The Oliver Chilled Plow Works, as such, ceased to exist on March 30, 1929. The executive office posts of the new Oliver Farm Equipment Company were divided among three of the merging companies, with J.D. as Chairman of the Board, a post he held until resigning on December 13, 1932.

J.D. Oliver died on August 6, 1933, in Copshaholm, the home that he had moved into with his wife, Anna Gertrude, and their young family in 1897. He was 83 years old.