Indiana and the Roaring Twenties

(This history is not intended to be a comprehensive or all-inclusive history of the state of Indiana. The History Museum provides this for general knowledge about Indiana’s history.)

Please note: The Ku Klux Klan is a domestic terror organization with a long history of violence and intimidation. Its racist ideology and actions have always directly opposed the fundamental truth that all people are created equal. The History Museum rejects any attempt to normalize or excuse such behavior and stands in solidarity with those targeted by hate and violence. The History Museum provides the following history to present a full accounting of Indiana’s history, hoping readers will realize history is not always pleasant and positive.

Navigate this page:

A majority of people already have a fixed image of the Ku Klux Klan in their minds. Men dressed in white robes and hoods, riding throughout the countryside harassing blacks. Most believe that the Klan is an extinct organization, once composed of rednecks and racist southerners.

However, unfortunately, the Klan is still alive in Indiana. There was a time in Indiana when Klan membership could help an aspiring political career. Leonard Moore from the University of California has carefully analyzed Klan membership documents of Indiana and discovered that 250,000 white men in Indiana (approximately 30% of the native-born Caucasian men in Indiana) joined the Klan in the early 1920s.

The Klan has appeared and disappeared over four times throughout its history. It is a constant bad dream for a free American society to deal with. Just when you think it has gone, it rears its ugly head once more. In its various forms and incarnations, the Klan has not entirely remained a southern-dominated organization. White supremacy has always been its goal; its anger and hatred have been used against other minority groups than just black Americans.

Its first appearance in American history was in the South, organized for only a short number of years between 1865 and 1872. The group was started by a group of 6 men from Pulaski, Tennessee, mainly as an elaborate game and roleplay of wearing eerie costumes while riding on horseback. It did not take long for the Ku Klux Klan (its name, supposedly, derived from the Greek word kuklos, which means “circle”) to go from a fraternal organization to a vigilante group bent on violence. An ex-Confederate general, Nathan Bedford Forrest, was chosen to be the Klan’s first leader.

Forrest headed up a committee that made the Klan a secret society with elaborate and, sometimes, bizarre titles: grand wizard, grand dragon, titans and cyclops. The Klan was filled with members of the recently defeated Confederate army. Their focus was threefold: to strike back at the federal Reconstruction government, to put the blacks “back in their place,” and to chase the white carpetbaggers back North. Because various southerners believed the North was using the Reconstruction to hand over the South to illiterate blacks, the Klan was a way for southern whites to strike back.

The first Klan attacked with a fierce vengeance. The first Klan set the violent tone for the future organization. Anyone, whether black or white, would meet a violent death if they stood in their way. The Klan’s tools of intimidation included lynching, shooting, stabbing and whipping. They perceived their mission as defenders of the white way of life. They also saw themselves as protectors of white women and the property of their birth. The federal government, however, saw them as criminals.

The government stepped in and ordered Nathan Forrest to disband the Klan. He reluctantly agreed, and the secret terror organization dissolved in 1869. However, violence towards blacks continued even after the dissolution of the Klan. The Klan’s reign of terror was temporarily over.

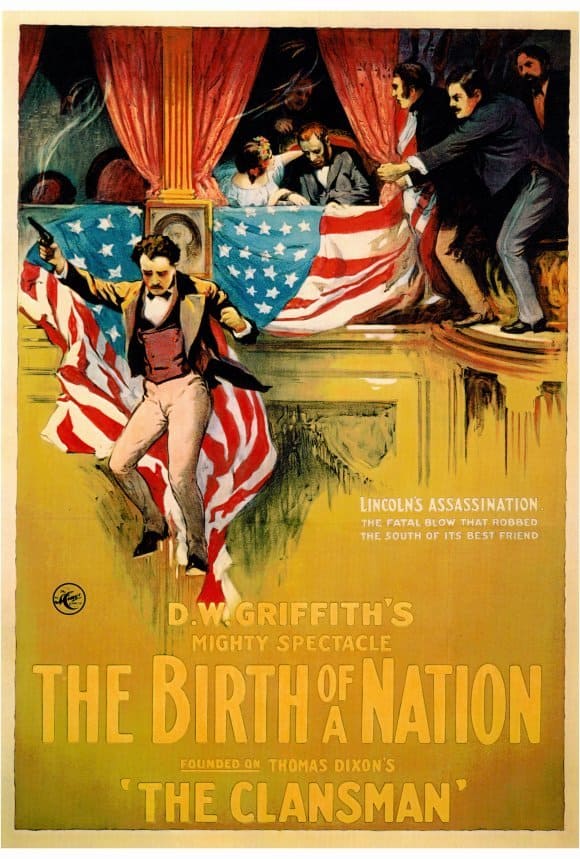

The Klan would have been forgotten if Thomas Dixon, Jr., a novelist, hadn’t produced a romanticized version of the Klan’s history. Dixon claimed the Klan was fighting for a just cause, defending their honor from wild blacks and white criminals. In 1915, almost 10 years after Dixon’s writings, filmmaker D.W. Griffith used his book as a basis for a new movie. The new movie was entitled Birth of a Nation, and it was praised in the South and crucified in the North. The South saw it as a true depiction of the raw deal of Reconstruction, while the North saw the film to legitimize racial hatred and violence toward minorities. However, when President Woodrow Wilson, a southern Democrat, saw the film and remarked that it was “all too terribly true,” the rest of America flocked to see this new epic.

When Birth of a Nation debuted in Atlanta, Georgia, on December 7, 1915, an advertisement appeared in the Atlanta

The first imperial wizard of the second Klan movement was a former Methodist preacher named William Simmons. He was interviewed in 1928 about why people joined this new Klan movement. Simmons said:

I went around Atlanta talking to men who belonged to other lodges [Masons, Woodmen of the World] about the new Ku Klux Klan. The Negroes were getting pretty uppity in the South along about that time. The North was sending down for them to take good jobs. Lots of Southerners were feeling worried about conditions. Thirty-four men belonging to various other lodges, promised to attend a meeting in [attorney E.R.] Clarkson’s office. And on the night of October 26, 1915, we met. They were all there. Two of them were men who had belonged to the old Klan. John W. Bale, speaker of the Georgia legislature, called the meeting to order. He was the first man in America to wield a Klan gavel. I talked for an hour and we all decided that the idea would grow. We voted to apply for a state charter.

In November 1915, Simmons and the new Klansmen held their first initiation ceremony and cross burning. With the Birth of a Nation providing free recruiting advertisement for the Klan, membership soared.

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, the Klan grew in strength. America now had to be ‘protected’ from the Germans and others: Catholics, Jews, Socialists, blacks and union leaders. Membership in the Klan was a way for citizens to help the war effort in Europe by making sure American soil was kept ‘pure.’ The Klan was quickly becoming something universal and not just a southern racist group. William Simmons now realized that the Ku Klux Klan could now become a national fraternal movement.

A man named Joe Huffington was chosen by Simmons and other top Klan officials to organize the Klan in Indiana. Huffington’s first base of operations was in Evansville, Indiana. In the late summer of 1920, he began preparing to bring the Klan to Indiana. It was not long before Huffington met a young man named D.C. Stephenson.

The Klan had a large vocabulary of secret words and titles that Stephenson had to learn. William Simmons was known as the imperial wizard, the top office of the Klan. Other office titles included: kligrapp, kludd, nighthawk and cyclops. Their secret meetings and gatherings were known as klonvocations. Membership fees were called klecktoken.

D.C. Stephenson, like all other new members, had to swear an oath of allegiance to the Klan and a vow of secrecy. New recruits were asked 9 questions:

Is the motive prompting your ambition to be a Klansman serious and unselfish?

Are you native born, white, Gentile, American citizens?

Are you absolutely opposed to and free of any allegiance of any nature to cause, government, people, sect, or ruler that is foreign to the United States of America?

Do you esteem the United States of America and its institutions above any other government, civil, political, or ecclesiastical in the whole world?

Will you, without mental reservations, take a solemn oath to defend, preserve, and enforce these same?

Do you believe in Klannishness and will you faithfully practice same toward your fellow Klansmen?

Do you believe in and will you faithfully strive for the eternal maintenance of White Supremacy?

Will you faithfully obey our constitutions and laws, and confirm willingly to all our usages, requirements, and regulations?

Can you always be depended on?

Did D.C. Stephenson take the oath seriously? No one knows. Stephenson’s public speeches are not filled with the racist rhetoric as many other leaders of the Klan. He usually left the hate speeches up to others in the power structure of the Klan. His talent was centered on organizing the Klan in Indiana and collecting new recruits.

Membership in the Indiana division of the Klan began soaring with each new speech that Stephenson made. As the group expanded to the western states and industrial cities of the Midwest, the Klan was no longer a southern sensation.

The Klan even made inroads into Indiana churches. The Reverend William Forney Harris of the Grand Avenue Methodist Church preached in 1922 that secret societies like the Ku Klux Klan would not get his support. However, these were times of “moral decay,” and as such, any organization that stood for decency and order ought not to be shunned. Other clergy offered similar endorsements to their congregations as the Klan membership grew locally.

D.C. Stephenson became a powerful political figure in Indiana. His rise to power was short-lived, however. In 1922, David Curtis Stephenson was appointed Grand Dragon of the KKK in Indiana. In 1925 he had met Madge Oberholtzer, who ran a state program to combat illiteracy, at an inaugural ball for Governor Ed Jackson. She was later abducted from her home in Irvington, a neighborhood of Indianapolis, and taken by Stephenson and some of his men to the train station. While on a trip to Hammond, Indiana, Stephenson repeatedly attacked and raped Oberholtzer in one compartment of his Pullman railcar. In Hammond, she took poison to frighten Stephenson into letting her go. He immediately rushed her back to Indianapolis, where she died a month later, either from the effects of the poison or the severe bite marks she incurred during the rape.

Stephenson was arrested and charged with second-degree murder. The sensational trial occurred in Noblesville, Indiana, in 1925. His conviction sent Stephenson to the Indiana State Prison in Michigan City, Indiana, for the next 31 years (the longest imprisonment in this state for that crime). He was released from prison in 1956 and faded into obscurity, but not before causing the shocking downfall of many corrupt political officials within Indiana. When he went to jail, he was convinced that Governor Ed Jackson, whom he had helped elect, would pardon him. Governor Jackson never came through with the pardon, and Stephenson began confessing and naming names.

With help from The Indianapolis Times (which won a Pulitzer Prize for its investigations), the structure of Indiana politics would be shaken. Stephenson discussed who had helped him rise to power and named names. The aftermath was shocking. Indictments were filed against Governor Ed Jackson, Marion County Republican chairman George V. “Cap” Coffin, and attorney Robert I. Marsh, charging them with conspiring to bribe former Governor Warren McCray. Even the mayor of Indianapolis, John Duvall, was convicted and sentenced to jail for 30 days (and barred from political service for 4 years). Some Marion County commissioners also resigned from their posts on charges of accepting bribes from the Klan and Stephenson.

This was not the image that Indiana wanted to portray during its “golden age.” Stephenson, at the peak of his political career and influence, had remarked, “I am the law in Indiana.”

Lutholtz, M. William. Grand Dragon: D.C. Stephenson and the Ku Klux Klan in Indiana. Purdue University Press: Lafayette, 1991.

Users may download material displayed on this site for noncommercial, educational purposes only, provided all copyright and other proprietary notices contained on the materials are retained. Unauthorized use of the Northern Indiana Historical Society d/b/a The History Museum’s logo and Web site logo is not permitted. The contents of this site may not be used for commercial purposes, without written permission of the Northern Indiana Historical Society d/b/a The History Museum. To obtain permission to reproduce information on this site, submit the specifics of your request in writing to Director of Marketing & Community Relations, The History Museum, 808 West Washington Street, South Bend, Indiana 46601 or If permission is granted, the wording “provided with permission from the The History Museum” and the date must be noted. However, permission is not required to create a link to the The History Museum’s Web site or any pages contained therein.