Local African American History

This history celebrates the richness of African American culture in the area known as the St. Joseph River Valley Region by highlighting historic places. These historic places remind us of the contributions made by African Americans to our community. Many buildings related to African American history no longer exist. Yet, information about these places lives on through historic records, photographs and newspaper articles. Another resource for learning about the people who built the buildings and the African American community is through stories their families share with us. Many local African Americans have saved their family histories and have shared the information with the community by donating historical documents to The History Museum, local universities (Civil Rights Heritage Center), and local libraries.

Although many early records have been lost or are incomplete, it is known that African Americans were among the early residents of St. Joseph County. They, like their neighbors, were often farmers or small business owners. Many of them were free Black men and women, and not fugitive slaves. Historical records show African Americans settled in St. Joseph County, Indiana, as the United States Government Land Office opened land sales in the early 1830s.

The 1850 U.S. Census lists the Huggarts, an African American family, as living in a remote rural section of Union Township in St. Joseph County, just south of South Bend. Other Black families followed them and settled nearby, creating what is thought to be the first rural Black settlement in northern Indiana. This part of Union Township was settled by both white and Black families, who shared in the community’s life. They farmed, worshiped, attended school and socialized together.

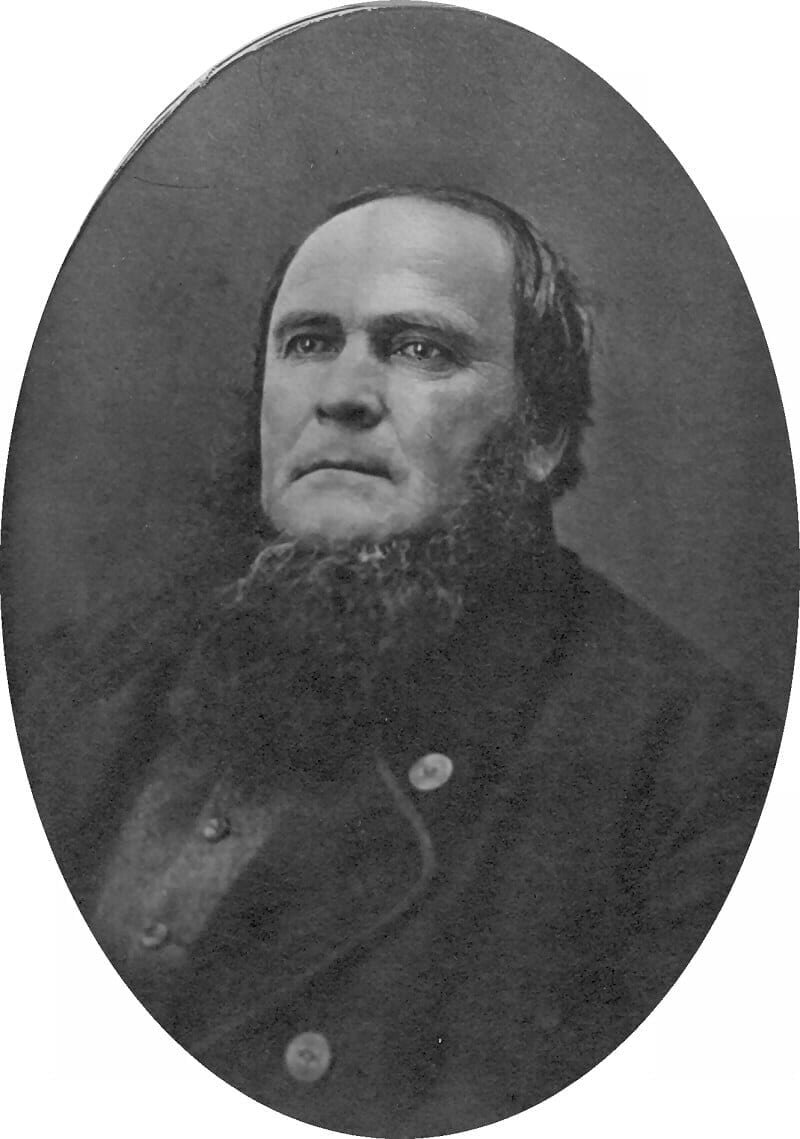

Samuel Huggart was a free Black man from Montgomery County, Ohio. He applied for land in Union Township on September 11, 1834. Several years later, he settled there with his family. In 1860, another Black man by the name of Benjamin Bass bought property next to the Huggart’s farm. Mr. Bass also purchased land in other parts of St. Joseph County, Indiana, and in Cass County, Michigan.

The settlement began with Samuel Huggart and was within a mile radius of two known Underground Railroad stations, one

In 1861, Hardy Manual purchased land from Mr. Bass and built a log cabin home that still stands in Union Township. Prior to moving to the rural settlement, Mr. Manual was a carpenter in South Bend. The cabin’s double dovetail corner joints testify to his woodworking skills.

The graves of many of the early Black settlers in St. Joseph County are in Porter-Rea Cemetery in Union Township. This cemetery was the final resting place for many neighborhood families, both Black and white. Today, the cemetery lies within the boundaries of Potato Creek State Park. In the 1970s, farmland around the cemetery was purchased by the State of Indiana for this recreation area. The cemetery today remains under the control of the Porter-Rea Cemetery Association, which was formed in 1888 by both Black and white families who lived in the area. Many burials pre-date the formation of the Association. Black settlement members and their descendants known to be buried at Porter-Rea Cemetery include: A.S. Boon, Rachel Boone, William H. Boone, Amanda Boone, Benjamin Boone, Jeanette Manual, Eliza Jane Manual, Samuel Huggart, Andrew Huggart, Jane Huggart, Maudie Huggart, Mary A. Huggart, Infant Huggart and Dila Bass.

Some of these tombstones can still be seen today.

The Huggart settlement dwindled in the 1890s as families moved into South Bend, where they found employment in the growing collection of industries.

In the 1840s and 1850s, many area citizens, both Black and White, were secretly involved in helping freedom seekers escape from the South. This complex system was referred to as the Underground Railroad. It was not an actual railroad, but a secret network of people willing to risk legal action and losing their own property to help slaves gain freedom.

Residents of St. Joseph County, Indiana, offered their homes, barns and businesses as “stations” or safe places in which runaways could eat and rest as they made their way north. Because of the secrecy of the Underground Railroad, many of the stations and their conductors will never be known.

Most notable among local Underground Railroad conductors was James Washington, a well-known and well-respected free Black in South Bend. Mr. Washington, a barber, and another barber, Mr. Sawyer, collected money from local citizens to fund the Underground Railroad. Mr. Washington’s barbershop was on Washington Street in downtown South Bend, over Bartlett’s Grocery and Bakery Store. Reminiscences by Charles Bartlett, the son of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Bartlett, tell of escaped slaves hiding in the family store in the 1850s.

Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Bartlett lived at 720 W. Washington Street. The women of Mrs. Bartlett’s reading and sewing circle donated money to support the Underground Railroad.

Most freedom seekers did not stay in St. Joseph County, because Indiana courts upheld fugitive slave laws and fined abolitionists who were caught helping runaways. These slaves were usually returned to the slave owner. With the help of local Quakers and others who were agents or conductors on the Underground Railroad, freedom seekers made their way north to Michigan and on to Canada, where freedom awaited.

There were many Quakers living in Cass County, Michigan, who helped the runaways and free Black people establish new lives. With the support of the Quaker community, former slaves became farmers or small business owners.

The Chain Lake Baptist Church is the oldest African American church in our region. It was established in the late 1830s. Here, people worshiped freely and celebrated their freedom. A walk through the cemetery at Chain Lake Baptist Church reminds us of the many African American families that have lived in this area for numerous generations. There is a historical marker at Chain Lake Baptist Church that tells of the role of the African American church in the antislavery movement.

In 1846, approximately 100 freedom seekers were in Cass County, primarily in Penn and Calvin Townships. In 1850, the U.S. Census for Cass County listed 389 free Black people living there. This Black community is still in existence today.

The area of Cass County known as Paradise Lake developed into a popular African American community. This beautiful lake

Local churches often baptized their members at Paradise Lake.

At the height of African American settlement in Cass County, the area offered the Gray Hotel, dining establishments, tennis courts, boating, swimming, horseback riding and other leisure activities. These facilities served both Black and white people.

Near the Calvin Community Chapel and the picnic area, you can find a cemetery where members of the local community were buried. Many of the family names on the headstones are the same as those found in the Nicholsville Cemetery in Volinia Township (Cass County, Michigan) and in the Porter-Rea Cemetery in Union Township (St. Joseph County, Indiana). This illustrates the strong relationship that has existed between African American families in these areas.

Along with the Calvin Center School, there was the Thompson’s Corner School. This was also a one-room schoolhouse where both Black and white students from the area attended school. The schoolmaster was Bert Riley. The school was at the intersection of Marcellus Highway and Lawrence Road.

In 1850, there were five Black families listed in the U.S. Census taken in South Bend. In 1858, Farrow and Rebecca Powell, their children and their grandchildren, bought properties and built homes in South Bend and Mishawaka, Indiana. Their homes were on the south side of South Bend, between South Michigan and Main Street. There were also Powell family members living around the Cedar Street area in Mishawaka. The Powells were very active in their church, Olivet A.M.E., as well as in the social and business life of the community. It is interesting to note that Elijah, Colonel and James Powell, sons of Rebecca and Farrow Powell, served in the Civil War. Colonel and James enlisted as white (they were very light-skinned).

Farrow (sometimes spelled Pharoah) and Rebecca Powell, along with many of the descendants of the William Bryant family, are buried in South Bend’s City Cemetery.

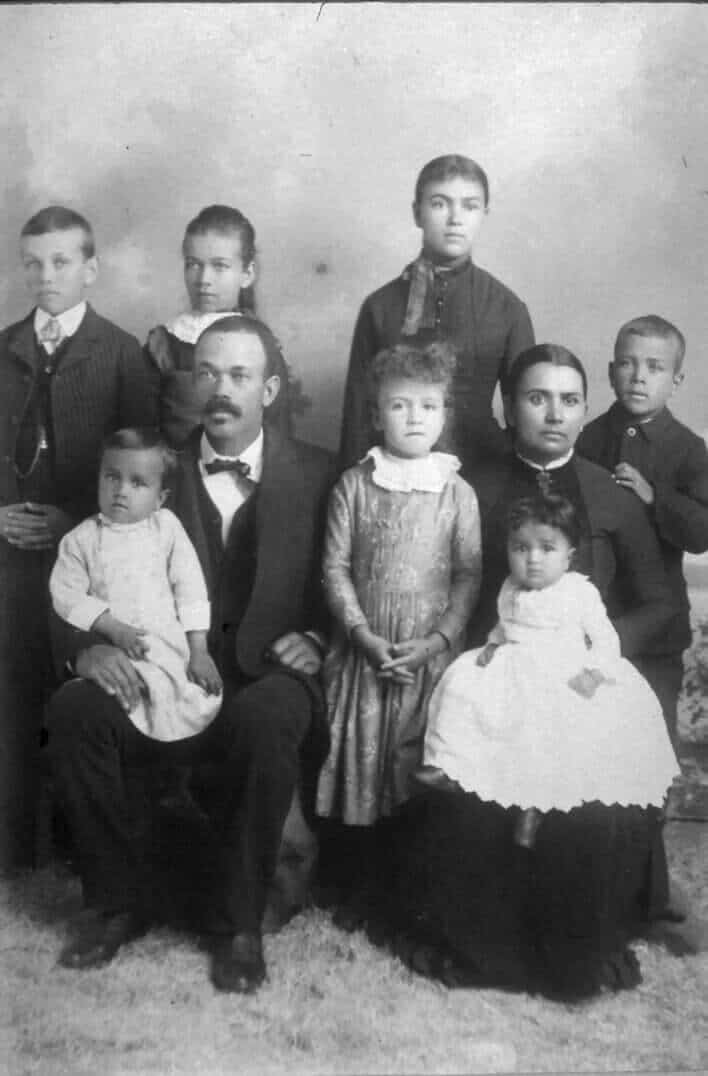

William & Julia Waldren Bryant family. Julia was related to the Powell family. Descendants of this family still live in the St. Joseph County area.

In 1973, students at Pierre Navarre School in South Bend spearheaded a community project to preserve the Powell house that stood at 420 South Main Street. The students, along with many community leaders and historians, wanted to preserve this historic home by moving it to Leeper Park near the log home of St. Joseph County’s first settler, Pierre Navarre. Unfortunately, the house was vandalized several times and finally set on fire and burned to the ground in 1980.

Religion has played a very important role in the history of the African American community. Traces of the early churches in South Bend can still be found.

The Olivet A.M.E. (African Methodist Episcopal) Church was the pioneer church in this area. It was organized in 1873 at 310 W. Monroe Street. The Powell family helped to organize the first African American church in South Bend. Today, Olivet A.M.E. is on the east side of South Bend at 719 North Notre Dame Avenue.

The second church built on this site replaced the wood-frame building. Today, it is the home of Zion Hill Missionary Baptist Church. It is most commonly seen beyond center field outside Four Winds Field-Coveleski Stadium in downtown South Bend.

Pilgrim Baptist Church, established in 1890, is the oldest African American Baptist Church in the city. At 116 N. Birdsell Street, it was originally the Mount Zion Baptist Church. The small wooden frame building was donated to the congregation by the Studebaker brothers. In 1941, the church was renamed Pilgrim Missionary Baptist Church.

Taylor’s A.M.E. Zion Church was organized in 1907. It was the only Black church on the east side of South Bend. Today, it is known as the First A.M.E. Zion Church at 801 North Eddy Street.

On West Washington Street in South Bend is a simple, white-framed church. St. Augustine’s Catholic Church was founded in 1928 and became the first fully integrated Catholic parish in the area. The people of St. Augustine’s have served the needs of the people who lived in the neighborhood.

Historical research proves that local African Americans organized and built numerous churches to serve their needs. Besides being a place to worship, churches have provided a place for social, cultural, educational and political activities.

Many early African Americans in the area were farmers and small business owners. The 1875 map of South Bend shows the East and West Races along the St. Joseph River in South Bend. Various businesses were located here because of the need for water power. The 1883 South Bend City Directory lists several Black men employed by local industries and Black women listed as domestics. By World War I, more and more African Americans were coming to the South Bend area to work in the growing number of industries in the area.

During World War II, new jobs were created because of growing industrial production for the war effort. The demand for workers was met by African Americans who moved to the South Bend area from southern states. Many African American professionals, such as doctors, dentists and lawyers, have lived in South Bend. Others have owned their own businesses, such as barbershops and hair salons, drug stores, funeral homes, restaurants, clothes cleaning establishments, groceries and hotels. The first African American doctors in the area were Dr. Hickman and Dr. Fears.

At the intersection of West Washington and Walnut Street in downtown South Bend were the offices of: Dr. C.A. Mott, Dr. V. Gibson, Dr. S. Vagner and Dr. F. Miller. Their office no longer exists. Dr. Casell Mott made house calls, and even after he retired, people sought him for medical advice. Dr. R. Chamblee and Dr. B. Streets also had offices on West Washington Street. Dr. Milton A. Butts’ office was in the same neighborhood at 118 North Walnut Street. Other doctors in the area were: Dr. W. Smith, Dr. H. Bell, Dr. G.P. Curtis, Dr. R. Love and his son, Dr. W. Love.

Rev. James L. Perry established his first pharmacy at 3503 West Washington Avenue and moved to 704 West Western Avenue in 1960. Mr. Perry operated the only Black pharmacy in South Bend.

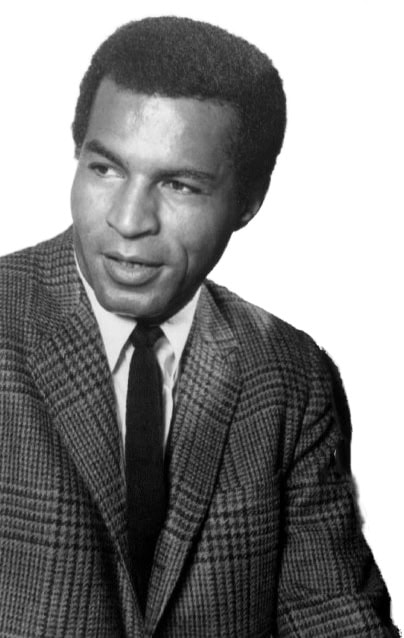

African American lawyers in the area were: J.W. Thomas, Maurice D. Pompey, Zilford Carter, Charles Wills, J. Chester Allen Sr., his wife, Elizabeth Fletcher Allen, Nola Allen Griffin, Charles Crutchfield and J. Chester Allen, Jr. Elizabeth Fletcher Allen was the first female lawyer in St. Joseph County and the State of Indiana. Along with her husband, J. Chester Allen, she helped form the Allen & Allen Law Firm, one of the first husband-and-wife teams in the area. Many years later, the Allens’ son, J. Chester Allen, Jr., joined their law firm.

J. Chester Allen, Sr., was born on Christmas Day 1900, and was the first African American to hold the following positions: president of the St. Joseph County Bar Association, state legislator and member of the South Bend City Council. He was the first African-American member of the South Bend School Board. Throughout his career, he was active in housing and civil rights issues, and served as attorney for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). J. Chester Allen, Jr., was the first African American to become a judge in St. Joseph County.

Many African Americans in the area were barbers. Ben Powell and Otto Powell had a barbershop in Mishawaka as early as 1869 on the west side of Main Street. John B. Lott, William Walker, James Jackson and others had barber shops in South Bend. One of these shops was described as having the entire upper floor with a bath and every modern convenience.

There were African American-owned hotels in South Bend, including the Wilder Hotel and the Liston Street Hotel, both on Liston Street. In the 1940s, next door to the Liston Hotel, was the Colmer Grocery Store, which was an African American-owned business.

The first Black school teachers taught at Linden School, at 1522 West Linden Avenue. They were Peggy Flowers Eskridge and Herbert Lewis, who were hired in 1950. Edward Myers became principal of Linden School in 1959 and remained there for 13 years. He retired in 1993 after 40 years of service to the South Bend schools. Land was purchased to build a new school on the old Linden School site, but because of a court case concerning de facto segregation, the school was never built. The land was purchased by the South Bend Parks Department from the South Bend Community School Corporation for construction of the Martin Luther King, Jr., Center.

Along with education, organizations and clubs have been a vital part of the African American community for many years.

Several African American clubs existed in South Bend. The St. Pierre Ruffin Club was organized in 1900 to stimulate culture and the study of literature. Our Day Together Club was organized in 1904 to promote charitable works and the study of good literature. Both clubs still exist today.

In 1925, Frank and Clarabel Hering gave the Hering House, often referred to as the “House of Hope,” to the African American community of South Bend. At 726 West Western Avenue, the Hering House served as a center for community activities until 1965, when it closed because of a lack of funding. Hering House promoted community and recreational activities for African Americans. Many clubs, such as the Teen Club, held meetings and sponsored special events at Hering House. The H.T. Burleigh music group presented annual spring operas and fall concerts.

Cherry Hall, near West Washington and Cherry Streets, was used for recreation and special events after Hering House closed in 1965. Many members of the community remember the teen dances that were held at Cherry Hall during the 1950s.

In 1989, Ladies of Distinction, Inc., was organized in South Bend to promote self-reliance, education and unity among people. In 1993, the organization published a calendar featuring African Americans who had made significant contributions to the community.

In 1840, the African American population of St. Joseph County was very small, with only nine Black people counted in the U.S. Census. The numbers grew slowly until World War I and then soared in the 1940s. The 2004 U.S. Census showed a total population of 265,559 with 30,422 African Americans (approximately 11.5% of the population) in St. Joseph County.

The African American community continues to make important contributions to the religious, economic, professional, educational and social aspects of Michiana. This brief history is only a glimpse of the rich African American heritage of this area.

The Free Life Theater features a 30-minute award-winning video documentary of the African American community in the St. Joseph River Valley region from the 1820s through World War I. A significant portion of the area focuses on Underground Railroad sites found in northern Indiana and southern Michigan. To watch this video documentary in its entirety, CLICK HERE.