(This history is not intended to be a comprehensive or all-inclusive history of the state of Indiana. The History Museum provides this for general knowledge about Indiana’s history.)

Navigate this page:

Beginning in the late 1930s, Germany, Italy and Japan made war on Poland, France, Great Britain, the Soviet Union and other countries. The United States stayed out of direct action in these conflicts until December 7, 1941, when the Empire of Japan led a surprise attack on the American Navy docked in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. The next day, the United States officially entered the war.

World War II affected and changed Indiana. The almost dormant steel mills in the northwestern part of Indiana went back to full operation, producing wartime material. The U.S. Steel factory along Lake Michigan began running 24-hours a day, 7-days a week. Many new factories were also built during this increase in wartime production. In Charlestown, Indiana, along the Ohio River, two factories were built specifically to build wartime goods, and suddenly the town’s population went from 890 people to 15,000 people!

Like what happened during the previous wars, Hoosier men and women joined the armed forces. Around 338,000 Indiana men fought in World War II, and out of these, 13,370 were killed during the war. Approximately 118,000 Hoosier women also served in the military.

During the war, there were numerous jobs that went unfilled throughout the state. Many women left their homes and found jobs in wartime production; this being the first time many of them had ever had a job outside of their home.

Because of the shortage of human resources, many disenfranchised blacks living in the South migrated in large numbers to the North, and many came into Indiana to find work. For many, this would be the first time they could work and learn a skilled trade.

Several areas of the state were used for training new military troops and for testing new military equipment. One of these large training and testing centers was Crane Ammunition Depot in Martin County. Crane Ammunition Depot was built on 63,000 acres of southern Indiana forest.

The American government began seeking properties where ammunition production could be started quickly. 13,000 acres in LaPorte County, Indiana, was eventually set aside for construction of the Kingsbury Ordnance Plant, because it had an ideal amount of flat land, fresh water, road and railroad access, and far from either coast in case of potential enemy attacks. It was also in a sparsely populated area and provided a place where an accidental explosion would not cause mass casualties.

Construction of the Kingsbury Ordnance Plant began in 1940, with factory buildings constructed as well as bomb shelters, offices, and barracks built on site. Housing was built for the over 20,000 workers needed to produce the artillery. Because so many men were involved in fighting the war, a majority of Kingsbury workers were women.

Women workers at the Kingsbury Ordnance Plant. Courtesy of the LaPorte County Historical Society Museum

Initially named “Victory City,” the plant construction planning for the town had begun simultaneously. Construction of nearly 3,000 on 775 acres began in 1942. Most of the houses built were one-story bungalows, and plans for the new community included schools, a civic center, police, fire, and medical facilities, and an administration center acting as a type of town hall.

Workers rented the newly built bungalows from the government; numerous workers still commuted to Kingsbury from their own homes, and postwar news reports showed that only around 300 of the newly built homes were occupied during World War II.

A current photograph of a few of the Kingsbury Ordnance buildings. Courtesy of The South Bend Tribune

As the war ended, production at Kingsbury naturally slowed and came to a halt. The plant was reopened briefly for the Korean War a few years later, but permanently closed and decommissioned by the government in 1960. In 1965, 7,000 acres were made the property of the State of Indiana and eventually converted to the Kingsbury Fish and Wildlife Area [CLICK HERE]. Other portions of the property were converted to an industrial park, and some were put back as farmland.

Victory required civilian sacrifice, not as large as the sacrifices made on the home fronts of Great Britain or the Soviet Union, but substantial sacrifices nonetheless.

Most apparent was the shortage and eventual rationing of numerous items considered basic to the good life. A complicated rationing system demanded coupons and points for the purchase of food, shoes, and gasoline. Some items, such as nylon stockings and new tires, virtually disappeared. With limited quantities of meat, sugar, coffee, and other foods, homemakers prepared meals with ingenuity in recipe substitution, patience in the grocery stores, and Victory Gardens in their backyards.

Gasoline was severely rationed. Many Hoosiers could no longer visit grandparents or a state park on Sundays. Both the Indiana State Fair and the Indianapolis 500-mile race closed under war demands. Even with a fat wartime paycheck, a new automobile was an unattainable dream until 1946. Many shade-tree mechanics spent tedious hours installing a used part to keep an old Ford, Chevy, Chrysler, or Studebaker running on bald tires.

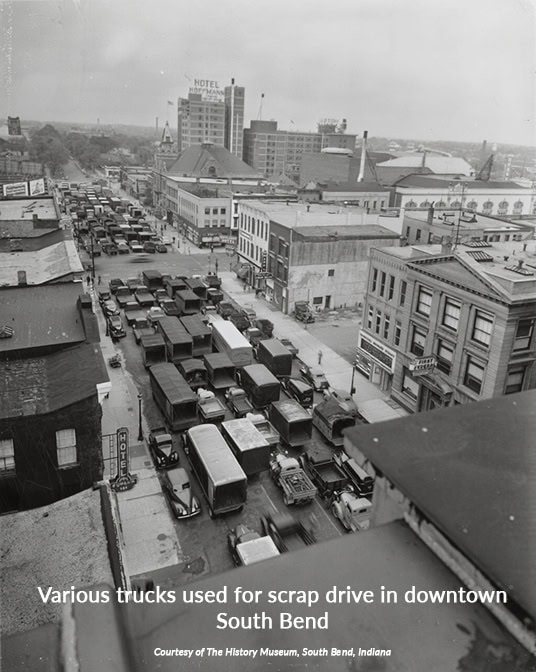

The war meant sacrifice for children too. Many would vividly remember for the rest of their lives the terror produced by blackouts and air-raid drills. Children eagerly joined in scrap drives that gathered metal, paper, and rubber for war production. They worked for war bond and stamp sales, studied maps of Europe and the Pacific, and played war games.

Young Hoosiers became the focal point of new concerns about family breakdown. Some children knew their fathers only as the fuzzy snapshot of a man in uniform. Many adults worried about what would happen with fathers away and mothers working in factory jobs. The war brought parents special anxieties about teenagers mixed up with alcohol, crime, or sex. One response was the formation of teen clubs to encourage more wholesome entertainment at places like South Bend’s Hi-Spot and Anderson’s Club Tom Tom. With an increasingly distinctive style of music, dress, and language, wartime teenagers created a life of their own, one separate from that of their baffled parents.

There was romance during the war. The Great Depression had delayed numerous marriages, but the war boom made marriage financially possible once again. Often, couples rushed to the altar just ahead of the departing troop train. Young war brides and new mothers made some of the home front’s greatest sacrifices, and in their V-Mail to distant husbands they scribbled some of the most poignant stories of these years.

Victory in 1945 brought the celebratory sounds of factory whistles, the shouts of street dancing, the bright colors of parades, and the shedding of tears. Many Hoosiers looked ahead to a return to prewar conditions, without, they hoped, the angry bear scratches of economic depression. Wartime conditions seemed to pass quickly after 1945. Rationing, shortages, and long lines vanished, replaced, for many, by an affluent society. Scrap drives and recycling soon seemed only distant memories of wartime sacrifice. Military uniforms and souvenirs made their way to attics. Numerous women and many black Hoosiers surrendered their high-paying industrial jobs to returning veterans, though not always willingly. And yet, life did not return to the patterns of 1941.

V-E Day celebration on Monument Circle, downtown Indianapolis. The Indianapolis Star

Ernest “Ernie” Taylor Pyle was born on August 3, 1900, on the Sam Elder farm near Dana, Indiana, in rural Vermillion County, Indiana. His parents were Maria and William Clyde Pyle. At the time of Pyle’s birth, his father was a tenant farmer on the Elder property.

Pyle enrolled at Indiana University, Bloomington, in 1919, aspiring to become a journalist. However, Indiana University did not offer a degree in journalism, so Pyle majored in economics and took as many journalism courses as he could.

Pyle left school in January 1923 with only a semester remaining and without graduating from IU. He took a job as a newspaper reporter for the Daily Herald in La Porte, Indiana, earning $25 a week. Pyle worked at the Daily Herald for three months before moving to Washington, D.C., to join the staff of The Washington Daily News.

Pyle initially went to London in 1940 to cover the Battle of Britain, but returned to Europe in 1942 as a war correspondent for Scripps-Howard newspapers. Beginning in North Africa in late 1942, Pyle spent time with the U.S. military during the North African Campaign, the Italian campaign, and the Normandy landings. He returned to the United States in September 1944, spending several weeks recuperating from combat stress before reluctantly agreeing to travel to the Asiatic-Pacific Theater in January 1945. Pyle was covering the invasion of Okinawa when he was killed in April 1945.

Pyle was buried wearing his helmet, among other battle casualties on le Shima, between an infantry private and a combat engineer. In tribute to their friend, the men of the 77th Infantry Division erected a monument that still stands at the site of his death.

Visit Ernie Pyle’s childhood home in Dana, Indiana, by CLICKING HERE

Madison, James H. Published in Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History, a publication of the Indiana Historical Society, Fall 1991, Volume 3, Number 4.

Users may download material displayed on this site for noncommercial, educational purposes only, provided all copyright and other proprietary notices contained on the materials are retained. Unauthorized use of the Northern Indiana Historical Society d/b/a The History Museum’s logo and Web site logo is not permitted. The contents of this site may not be used for commercial purposes, without written permission of the Northern Indiana Historical Society d/b/a The History Museum. To obtain permission to reproduce information on this site, submit the specifics of your request in writing to Director of Marketing & Community Relations, The History Museum, 808 West Washington Street, South Bend, Indiana 46601 or If permission is granted, the wording “provided with permission from the The History Museum” and the date must be noted. However, permission is not required to create a link to the The History Museum’s Web site or any pages contained therein.